Regulatory Rapporteur

September 2025 | Volume 22 | No.8

Abstract

The e-PIL pilot was set up in 2018 in Belgium and Luxembourg with the objective of demonstrating the equivalence between the paper patient information leaflet (PIL) and the electronic version of this leaflet in providing information on the safe and effective use of medicines in the hospital setting. The results of the pilot demonstrate this equivalence. Additionally, it shows that the absence of the paper leaflet has a positive impact on pharmacy waste management and does not result in any inconvenience in pharmacists’ daily work. Most of the responding hospital pharmacists would agree to the removal of the paper leaflet from all hospital-only medicines. The data supports a potential change in European pharmaceutical legislation introducing the concept of electronic product information (ePI).

Licence notice

Copyright © 2015-2025 The Organisation for Professionals in Regulatory Affairs Ltd. T/A Regulatory Rapporteur − All Rights Reserved. This work is licensed to Pharma.be vzw for commercial use.

Notwithstanding this licence, no part of materials published in Regulatory Rapporteur may be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher.

As a general rule, permission should be sought from the rights holder to reproduce any substantial part of a copyrighted work. This includes any text, illustrations, charts, tables, photographs, or other material from previously published sources.

To obtain permission(s) to re-use content published in Regulatory Rapporteur please email publications@topra.org.

To join TOPRA please click here.

The electronic PIL: A fast, efficient and environmentally-friendly option

In the EU, every medicine package must currently include the paper PIL, which contains regulated and scientifically approved information to ensure the proper use of the medicine.[1][2] Furthermore, the latest approved version of the PIL is available electronically on the regulator’s website. The European pharmaceutical legislation is currently under review. The proposed revision includes the introduction of ePI, paving the way for a future transition from paper-based patient information to an electronic version of this patient information.

Why use the electronic version of the PIL?

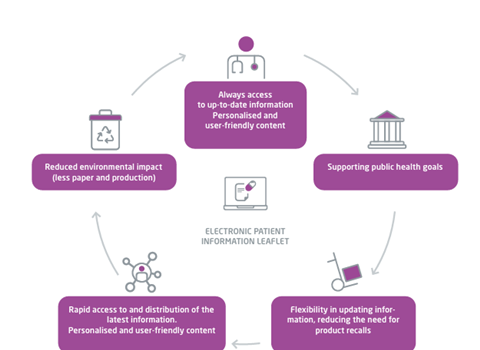

The introduction of an electronic version of the PIL offers several distinct advantages compared to the traditional paper-based PIL, benefitting both patient care and regulatory processes. An electronic PIL provides patients and healthcare professionals (HCPs) with immediate access to the latest product information, made available by marketing authorisation holders (MAHs) and the regulatory authorities responsible for the relevant jurisdiction. The electronic format allows both patients and HCPs to access information tailored to their needs (for example, in their language of choice and with the ability to electronically search for topics of interest), which enables stakeholders to make more informed decisions (Figure 1).

From a regulatory perspective, adopting an electronic format of the PIL can streamline processes for both the pharmaceutical industry and competent health authorities. It enhances efficiencies in the end-to-end review, approval and dissemination of product information in general.

Figure 1: The advantages of an electronic version of the PIL

Why is there a need to phase out paper-based patient information?

Replacing the paper PIL with an electronic version could positively impact medicine availability. While recalls to update the paper PIL are relatively rare, removing the need for such recalls would be beneficial. Moreover, the use of the electronic version of the PIL would facilitate imports between countries in Europe, which can also improve availability. The shift would additionally benefit the environment, since adding the paper PIL in the packaging requires many additional resources such as paper, ink, larger packaging, and consequently more space and weight for transport and storage.

When considering the replacement of the inserted paper PIL in the packaging by its electronic version, the electronic version must be at least equivalent to the paper PIL in providing patients and HCPs with information on the safe and effective use of the medicine. In 2018, an e-PIL pilot was implemented to demonstrate this equivalence, in a stepwise approach starting in all hospitals in Belgium and Luxembourg.

The Belgian and Luxembourg e-PIL pilot[3]

The hospital e-PIL pilot was proposed and designed by the associations of the (bio)pharmaceutical industry in Belgium (pharma.be) and Luxembourg (IML). The pilot had the support and collaboration of the Federal Agency of Medicines and Health Product (FAMHP) in Belgium and the Direction de la Santé (Ministry of Health) in Luxembourg, and the agreement of the European Commission (EC). This pilot is supported by the professional associations of hospital pharmacies in Belgium (BVZA-ABPH) and Luxembourg (APHL) and, since 2020, by Medaxes, the association for generic and biosimilar medicines.

The concept and objective of the e-PIL pilot

For seven years, the pilot has tested the transition from the paper PIL to the electronic version of the PIL in selected hospital-only medicinal products available on the Belgian and/or Luxembourg markets. The paper PIL was no longer inserted in the medicine packaging. Instead, HCPs were referred to its electronic version, which was available on various trusted online sources, as listed below:

- The pharma.be e-compendium

- The FAMHP website (FarmaInfo)

- The Belgian Center of Pharmacotherapeutic Information (CBIP) website

The medicines were proposed on a voluntary basis by the MAHs, and their participation was validated by the national competent authorities (NCAs) of both countries. By default, all hospitals in Belgium and Luxembourg participated in this pilot, to avoid complexity from the perspective of MAHs to release different hospital-depending batches (with/without paper PILs inserted in the packaging).

The objective was to demonstrate that the electronic version of the PIL is at least equivalent to its paper version in providing patients and HCPs with information on the safe and effective use of medicines in a hospital setting.

To conduct this pilot, a specific derogation from the legal requirement of inserting the paper PIL was requested and obtained from the EC. Initially approved for two years starting in August 2018, the pilot was extended for an additional five years based on positive interim results, and concluded in August 2025.

Methodology of the e-PIL pilot

In June 2018, a dedicated steering committee, consisting of representatives from the NCAs, the hospital pharmacy associations and the pharmaceutical industry was created to define and validate the key performance indicators (KPIs) of the pilot. The steering committee also monitored the pilot and analysed the KPI results.

The following KPIs were chosen:

- The conduct of a survey at specific times (at the start, after 12 months, after 24 months, after 48 months and after 72 months), to evaluate the access, use and reading of the electronic version of the PIL. The survey was primarily for participating hospital pharmacists but also aimed to capture the feedback of other HCPs (such as physicians and nurses) in hospitals

- The conduct of a survey at specific times (after 12 months, after 24 months after 48 months and after 72 months) of the participating pharmaceutical companies, to evaluate any questions received due to the absence of the paper PIL within the concerned medicines

The survey questions were developed under the supervision of the steering committee. Distribution was carried out electronically: surveys for hospital pharmacists were disseminated via hospital pharmacy associations, while those for pharmaceutical companies were shared through industry associations. The questions are further explained below.

More than 120 medicines, restricted to hospital use, from 27 pharmaceutical companies, were included in the pilot.

The first results of the e-PIL pilot

These are the baseline results (t=0) with a response rate of 100% in Luxembourg and 92% in Belgium.

The first survey was conducted at the beginning of the pilot in 2018, and explored the experiences and views of participating hospital pharmacists in order to create a reference baseline for the access, usage and reading of the already available electronic PIL via existing trusted online sources.

The survey revealed that 72% of hospital pharmacists consulted patient information in their daily practice on a daily or weekly manner, regardless of whether paper or electronic. It was determined that primarily, patient information was used to answer questions from HCPs (physicians, nurses and other pharmacists) or hospital departments, to check the posology (for example, in case of pregnancy), the indication, the instructions for the preparation or administration, interactions with other medicines, adverse events and storage conditions. This was especially important for new medicines or medicines for rare diseases. 75% of hospital pharmacists consulted the electronic version of the PIL either daily or weekly. Moreover, 78% of hospital pharmacists indicated that their rate of consulting the paper-based PIL had fallen to less frequently than every six months or not at all.

The baseline survey also revealed that 91% of hospital pharmacists were either ‘never’ or ‘less frequently than every six months’ asked by patients for the PIL of their medicines administered in hospitals. In these rare situations, the patients were provided with either the paper PIL (52%) or a printout of the electronic version of the PIL (37%).

The final results (after 72 months)

These are the final results of the survey in hospital pharmacies (t=72 months) with a response rate of 75% in Luxembourg and 57% in Belgium.

In hospital settings, according to 68% of the hospital pharmacists who responded, only the SmPC is used by the different HCPs compared to the PIL. If the PIL is used, this is mainly by nurses (24%), followed by hospital pharmacists (10%).

In practice, 87% of the responding hospital pharmacists had to consult the PIL of the medicines in the pilot every 6 months or less, and 8% had to consult the PIL monthly. For these consultations, 97% accessed the online version directly, and only 3% printed the leaflet from the online source.

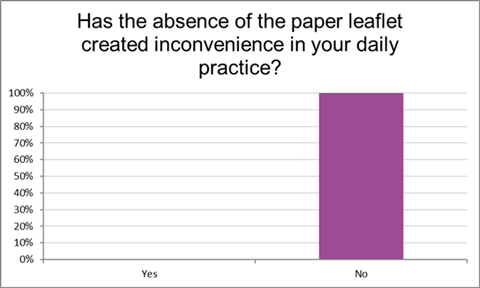

For all the responding pharmacists (100%), the absence of the paper PIL in the packaging of the medicines included in the pilot had not generated any inconvenience to their daily practice (Figure 2). Furthermore, according to 100% of the pharmacists, the absence of the paper PIL did not cause any inconvenience for the physicians, and according to 97% of the pharmacists, the absence did not cause any inconvenience for the nurses.

When the electronic PIL was consulted, a large majority of the responding hospital pharmacists (85%) preferred to consult the information in a structured format (for example, chapter by chapter) over a non-structured format such as plain text.

Figure 2: Inconvenience generated by the absence of the paper PIL on the daily practice of the pharmacists

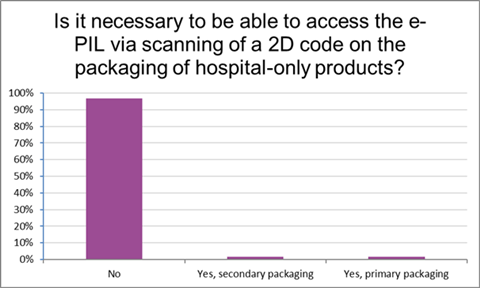

When asked whether accessing the electronic version of the PIL via a 2D code on the packaging for hospital-only products was necessary for their daily work, 97% of responding pharmacists said it was not (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Necessity of access to the electronic PIL via scanning of a 2D code on the packaging of hospital-only products

The results of the final survey after 72 months in the pilot showed that the patient very rarely solicited the hospital pharmacists directly to receive the PIL for medicines given in a hospital setting. In those very rare cases when it had happened with the medicines included in the pilot, the patient had been given, in approximately half of the cases (56%), a printed version of the PIL and in just less half of the cases (44%) the online version.

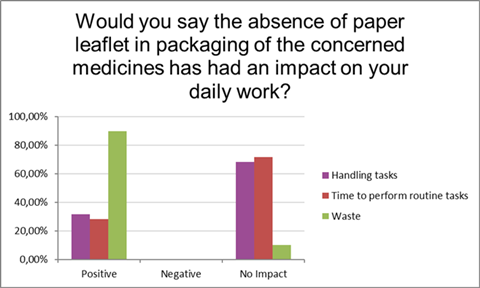

Moreover, the absence of the paper PIL in the packaging of the medicines in the pilot had either no impact (68%) or a positive impact (32%) on the handling tasks of the responding pharmacists in their daily work (Figure 4). It had no impact (72%) or a positive impact (28%) on the time required for pharmacists to carry out routine tasks, such as retrieving the primary packaging from the secondary packaging, without having to remove a paper PIL. Furthermore, it had a positive impact (90%) on the management of paper waste in the pharmacy.

These results confirmed the fact that the absence of the paper PIL in the packaging of the medicines in the pilot did not generate any inconvenience in the daily work of the responding pharmacist, and in some cases even made their tasks easier.

Figure 4: Impact of the absence of the paper leaflet in packaging on the daily work of the pharmacists

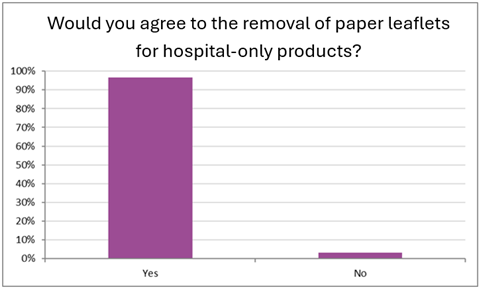

Consequently, 97% of the responding pharmacists felt that they would agree to the paper PIL being removed from the packaging of the medicines restricted to hospital use (with no ambulatory delivery/use) (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Pharmacists’ view on the removal of the paper PIL for hospital-only products

Pharmaceutical company survey results (t=72months)

This survey showed that, for an aggregated total of 4,290,712 sold units during these 72 months, only 12 questions were submitted to the pharmaceutical companies by HCPs and these were mainly related to the presence of a blank leaflet in the carton of some of the medicines participating in the pilot. This was out of concern for the physical integrity of the vial within the packaging. It should be noted that this was a temporary solution and, in the long term, the packaging would be redesigned to maintain vial integrity without the need for a blank leaflet. Providing information about the pilot project was a sufficient response for the HCPs and, in only one case, the paper PIL was sent to the healthcare professional.

The survey also captured the challenges that were encountered by the pharmaceutical companies during the execution of the pilot. One of the main difficulties was that phasing out the paper PIL required changes to packaging procedures. This, in turn, generated the need for change controls and some validation of new processes. Additionally, in some cases, the removal of the paper PIL necessitated resizing or redesigning the packaging carton.

These adaptations are particularly challenging given the temporary nature of the pilot and its limited number of participating countries.

Conclusion

The analysis of the final results after 72 months, combined with the baseline data, demonstrated that, in a hospital setting, the exclusive use of the electronic version of the PIL is equivalent to the use of the paper PIL in providing information on the safe and effective use of medicines by hospital pharmacists and HCPs in their daily practice.

The pilot clearly showed that, in the daily practice of hospital pharmacists, the electronic version of the PIL was consulted online without the need to obtain a printout. Moreover, the absence of the paper PIL had either no impact or even a positive impact on the responding pharmacists’ handling of the medicines.

Overall, the results illustrated that the absence of the paper PIL in the medicine packaging did not cause any inconvenience to the daily work of the pharmacist, and was even found to ease the burden of the pharmacists’ daily work. Moreover, the pilot revealed that the absence of the paper PIL did not cause any inconvenience for physicians or nurses in the hospital setting. The results also demonstrated that direct requests from patients to consult the PIL for their medications in the hospital setting were very rare.

Next steps for the pilot

As part of the ongoing revision of pharmaceutical legislation, the EC aims to enable the transition from paper to ePI. The final empirical results of the pilot in Belgium and Luxembourg could support the decision to change legislation and allow the use of electronic version of the PIL for medicines administered in hospitals.

The EC has given the green light to the Belgian and Luxembourg authorities to allow the continued absence of the paper PIL for those medicines that participated in the pilot until the implementation of ePI within the framework of revised pharmaceutical legislation.

In the meantime, the Belgian biopharmaceutical industry is keen to continue preparing for the transition to ePI in a broader scope. The NCA in Belgium is currently bringing together all involved stakeholders to explore the possibility of setting up a pilot outside the hospital environment. This will allow Belgium to optimally prepare for the transition from paper PIL to the electronic version of the PIL.

A hospital pharmacist perspective on the e-PIL pilot: Five questions to Katy Verhelle

Katy Verhelle is Chief Pharmacist at AZ Groeninge and the psychiatric hospital Heilige Familie in Kortrijk, Belgium. With extensive experience in hospital pharmacy spanning over three decades, she plays a pivotal role in the operational and clinical management of pharmaceutical services. She was an active board member of several professional associations, including the Belgian Association of Hospital Pharmacists (BAHP), the Flemish Association of Hospital Pharmacists (VZA), and the Advisory Board of BD Dispensing. Her work focuses on advancing digitalisation and automation in hospital pharmacy, medication safety and sustainable pharmaceutical practices.

What has been your experience of the e-PIL pilot, particularly in relation to the removal of paper leaflets from hospital medicine packaging?

In our hospital setting, the removal of paper PILs from the packaging did not represent a significant change in our way of working. It is standard practice to remove the outer packaging and accompanying leaflets upon receipt of the medicinal products, as we dispense medicinal products in single doses in the hospital. Consequently, the PIL is not typically available to physicians or nurses at the point of medicinal product administration. The information is instead accessed electronically via the hospital’s electronic patient record system or through national databases such as Farmainfo[4] and CBIP/BCFI.[5] The pilot project was thus well aligned with our existing practices.

The main challenges, though not limited to the pilot setting, lay in ensuring that patients, particularly those who are too sick or lack access to digital tools, can retrieve the necessary information about the medicinal products they receive. In our hospital, we address this by providing access to official sources online and/or offering printed leaflets on demand. However, in practice, patients rarely request the leaflet.

How did other healthcare professionals in your hospital, such as physicians and nurses, react to the pilot?

Physicians and nurses did not generally realise that the paper PIL had been removed from the packaging. This is because they do not typically handle the original packs of medicinal products in the hospital and, as mentioned previously, they receive ready-to-use or single-dose preparations from the pharmacy, with no paper PIL. The product itself includes essential information such as the name, dosage and administration route, while the full leaflet is accessed online.

Healthcare professionals are used to consulting digital tools such as the electronic patient record and the national databases (CBIP/BCFI).[5] These systems provide immediate access to the most recent version of the PIL, which is essential for safe and effective use of the medicinal product. As such, the pilot had no negative impact on their workflow and could be considered a neutral or even positive experience.

Did the pilot project have any implications for your daily pharmacy operations, particularly in terms of medicine handling or waste management?

The operational impact was minimal. Initially, pharmacy technicians noticed the absence of the paper PIL and flagged it as unusual, but this was quickly clarified. Good communication was key at the start of the pilot.

The only concern we encountered was that the paper leaflet sometimes plays a secondary role in stabilising vials within the packaging. Without it, handling the contents can become more delicate, increasing the risk of product damage. This highlights a need for adjustments in packaging design, but this is something that can be addressed beyond the scope of a pilot setting.

In terms of waste, the reduction in paper is relatively small per unit of medicinal product, but if implemented more broadly, the cumulative effect could be significant. We already manage large volumes of cardboard and paper waste, so any reduction is welcome. The pilot supports our sustainability goals, although the impact on waste volumes from leaflets alone is modest.

What is your perspective on the future of ePI in hospital settings?

The move towards ePI is consistent with broader efforts to improve the clarity and accessibility of patient information. Traditional PILs are often lengthy and difficult to understand, which discourages patients from reading them. As a result, healthcare professionals (associations) frequently create simplified summaries to convey essential information and improve reading by the patients.

In our hospital, we already provide project information files (PIFs) and other tailored materials to support nurses’ explanations to patients and to aid patient understanding. A structured electronic format of the PIL could further enhance this by enabling targeted/personalised information retrieval; for example, specific guidance for pregnant patients or preparation instructions for nurses. This would support more personalised and efficient communication about the medicinal product.

To conclude, based on your experience, would you support the broader implementation of ePI in hospital settings?

Yes, I would support the removal of paper PILs for medicinal products administered exclusively within the hospital. In such cases, the information is already accessed electronically, and the paper PIL is redundant. However, I would advise caution for medicinal products dispensed to outpatients, to whom the full packaging is provided.

The distinction between inpatient and outpatient settings is still important today. For outpatients of the hospital pharmacy, the experience is more similar to that of a community pharmacy, where patients are familiar with receiving the full packaging of a medicinal product with the paper PIL inside.

Therefore, while I support the broader implementation of ePI in general, a first essential step to move forward in outpatient settings is to ensure that patients are adequately informed about, and supported in, accessing electronic PIL.

Want to know more about this topic? Join our upcoming CRED An Overview of Regulatory Product Information course that will explore the development of regulatory product information in Europe and the UK, including the SmPC and the labelling and package leaflet.

References

[1] European Parliament and Council (2001). Article 58 from ‘Directive 2001/83/EC of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use’. (Accessed: 15 August 2025).

[2] European Parliament and Council (2001). Articles 11 ,54, 55 and 59 from ’Directive 2001/83/EC of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use’. (Accessed: 15 August 2025).

[3] Pharma.be (2025) ‘Evaluation of the pilot survey for hospital pharmacists to evaluate the access, use and reading of the EPIL’. (Accessed: 15 August 2025).

[4] FAMHP. ‘FarmaInfo’. (Accessed: 15 August 2025).

[5] Centre Belge d’Information Pharmacothérapeutique (CBIP) (2025) ‘CBIP – Informations fiables sur les médicaments’. (Accessed: 15 August 2025).