In the EU, the development of medical devices is supported by the European Commission Directive (93/42/EEC Medical Devices Directive). To this, the EU has a unique system in dealing with medical devices, iconised as the CE Marking, which provides the right for the products to be commercialised in the EU. This continuing professional development supplement presents the unique system of medical devices that is currently applied in the EU. Additionally, the new regulation of medical devices (EU 2017/745 Medical Device Regulation) is also covered.

Introduction

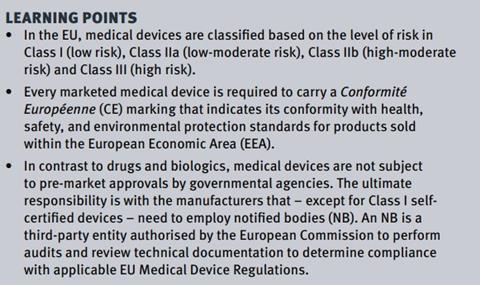

In the EU, every marketed medical device is required to carry a Conformité Européenne (CE) marking that indicates its conformity with health, safety, and environmental protection standards for products sold within the European Economic Area (EEA). There are three European Commission (EC) directives that have been subject to periodic amendment, which historically constituted the core legal framework for medical devices:[1]

- Council Directive 90/385/EEC on Active Implantable Medical Devices (AIMD)

- Council Directive 93/42/EEC on Medical Devices (MDD)

- Council Directive 98/79/EC on In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices (IVDMD)

Under Directive 93/42/EEC, the definition of a medical device is “any instrument, apparatus, appliance, material or other article, whether used alone or in combination, including the software necessary for its proper application intended by the manufacturer to be used for human beings for the purpose of diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of disease; diagnosis, monitoring, treatment, alleviation of or compensation for an injury or handicap; investigation, replacement or modification of the anatomy or of a physiological process; control of conception; and which does not achieve its principal intended action in or on the human body by pharmacological, immunological, or metabolic means, but which may be assisted in its function by such means”.

Classification in the EU

As early as the conception and design step, manufacturers should be able to identify the device classification via consultation with Annex IX of the EU Medical Devices Directive. The intended purpose of the device determines the classification rather than the particular technical characteristics. The classification is conducted by following a set of rules and combining different criteria relevant to the devices such as the duration of contact with the body (transient, short term, and long term); the degree of invasiveness (non-invasive, invasive, surgically invasive, and implantable); and the part of the body affected by the use of the device (Table 1).

Conformity assessment process of CE marking

At least three principal parties play important roles in the process of obtaining the CE marking for a medical device:[3], [4] ,[5]

- Competent authorities (CA) are appointed by the government of each European member state to ensure compliance with regard to the Medical Devices Directive (MDD) (see Table 2)[6]

- Notified bodies (NB) are designated by a CA to assure that the conformity assessment procedures are met according to the relevant criteria

- Authorised representatives (RA), if necessary, are appointed by the manufacturers as their legal representative and bear a legal responsibility to fulfill compliance with the regulations in place. An RA is required when a manufacturer is based outside the EEA.

When a manufacturer produces what is considered a medical device according to the MDD in place, relevant harmonised standards (HS) must be identified by the manufacturer.[7] HS consist of technical specifications established by several standard agencies, such as the European Committee for Standardisation (CEN), European Committee for Electrotechnical Standardisation (CENELEC), and ISO. Some examples of technical specifications that constitute the HS include the procedures and results of tensile test, bench test, corrosion behaviour, biocompatibility assessment, sterilisation procedure, and labelling. Moreover, the manufacturer would normally apply ISO 13485 standard that serves as a comprehensive quality management system for the design and manufacture of medical devices.[8]

| Class I |

|---|

| Generally consists of low risk and non-invasive devices such as devices used to immobilise a body part (cervical collar), devices intended in general for external patient support (eg, hospital bed, walking aids, wheelchairs, stretchers), corrective glasses, stethoscope for diagnosis, incision drapes, conductive gels, sterile dressings, and gloves. There are two sub-categories for Class I devices, including Class Is (sterile devices) and Class Im (devices with measuring function) in which they are regulated differently from regular Class I devices. |

| Class IIa |

| Constitutes low to medium risk devices and they mainly come into contact with the human body on a short-term basis. Class IIa devices are generally invasive, although limited to natural orifices. They undergo energy exchange with a patient in a therapeutic manner or are used to diagnose or monitor medical conditions. Examples of devices that fall under the Class IIa category include blood transfusion tubes, catheters, antistatic tubing for anesthesia, anesthesia breathing circuits, pressure indicator, pressure limiting, surgical blades, suction equipment, etc. |

| Class IIb |

| Generally includes medium to high risk devices and mostly come into contact with the human body on a long-term basis. Most of the Class IIb devices are surgically invasive or active devices that are partially or totally implantable in the body. Class IIb devices may also modify the composition of body fluids. Examples of Class IIb devices include a haemodialyser, gradient medium for sperm separation, haemodialysis concentrates, ventilators, radiotherapy equipment, etc. |

| Class III |

| Consists of strictly high risk devices that sustain human life and are substantially important to prevent the impairment of human health. Class III devices are mostly connected in a direct manner either with the central circulatory system, the central nervous system, or contain a medicinal product. Examples of Class III devices are cardiovascular catheters, biological adhesives, aneurysm clips, spinal stents, prosthetic heart valves, drug-eluting cardiac stents, pacemakers, etc. |

Once the HS and ISO 13485 have been applied, the manufacturer might want to contact a NB to have the preliminary discussion and exchange of information. The manufacturer needs to satisfy specific NB questions and work together with the NB regarding the confirmation of the device classification, the choice of certification route, and the estimation of cost and time for different certification routes depending on the devices. Subsequently, the manufacturer needs to submit a formal application to the NB to conduct an audit of the manufacturer’s operations and supplier’s and/or subcontractor’s facilities, as applicable. Following a positive decision from the NB, the manufacturer needs to affix the CE marking on the device and provide the Declaration of Conformity. The manufacturer is subsequently subject to a surveillance audit and is required to conduct a full audit five years following the issuance of the CE marking certificate.[9]

The type of device plays a significant role in the conformity assessment procedure to obtain the CE marking. Although each class of device is required to satisfy different requirements, all medical devices are required to provide a technical file (documentation) to support conformity assessment.7 The technical file consists of essential information concerning the medical device, such as the general description of the product, design drawings, and, if applicable, sterilisation method, and preclinical and clinical evaluation. A technical file serves as evidence of compliance with the essential safety and health requirements as listed in the MDD and it must be made available to the CA.[7]

Class I device manufacturers are eligible for a self-declaration route in which the manufacturers formally declare by written statement (Declaration of Conformity) that their products satisfy the applicable provisions of the Directive. However, Class I and Class Im devices are partially certified to fulfill CE marking conformity requirements with regard to their sterility and metrology standards, respectively.[3]

Class IIa device manufacturers are required to conduct a conformity assessment carried out by an NB. Subsequently, the manufacturers can declare conformity with the provisions of the Directive and ensure that the products comply with relevant essential requirements.[3]

Class IIb device manufacturers are required to undergo a compliance route similar to Class IIa with an additional NB conformity assessment. Manufacturers of Class IIb devices may also choose the full quality assurance route that includes assessment by an NB of the technical documentation for at least one representative sample for each generic device group for compliance with the Directive.[3]

Class III device manufacturers are required to include a full quality assurance system audit along with the examination of both the device’s design and the device itself by an NB.[3]

Post-market regulations

Council Directive 93/42/EEC on Medical Devices authorised marketing “without further controls and no further evaluation”, but subsequent 2010 regulations tightened requirements for the approval of devices based on their similarity to the predicates. They also required the manufacturer to conduct a “proactive post-market surveillance”.[10]Post-marketing surveillance events (eg, alerts, modifications, recall, and withdrawal of products) are also required to be reported to a central database (Eudamed) to facilitate dissemination of information of adverse events throughout Europe.[11] The database is currently available only to the EC and CAs, not to the public.

Failure of a manufacturer to comply with the post-market regulation can result in criminal penalties. Penalties for non-compliance differ significantly, depending on the member states.[12]

Future changes

Problems with diverging interpretation of the current Directives, as well as the incident concerning fraudulent production of the PIP silicone breast implants (see case study overleaf), highlighted weaknesses in the legal system in place at the time and damaged the confidence of patients, consumers, and healthcare professionals in the safety of medical devices.[13] On April 2017, two new EU laws concerning medical devices and in vitro diagnostic medical devices were adopted: EU 2017/745 and EU 2017/746, respectively.[14] These regulations replace EU directives which had become outdated due to the rapid pace of technological advances and changing patterns of medical practice. The new regulations will be applied from 2020 for medical devices and from 2022 for in vitro diagnostic medical devices. They will govern all aspects of the lifecycle of medical devices, from initial market approval to post-market surveillance.

Among important improvements of the new regulations are:

- Increased ex-ante control for high-risk devices via a new pre-market scrutiny mechanism involving a pool of experts at the EU level

- Reinforcement of the criteria for designation and processes for oversight of the NB

- Improved transparency through the establishment of a comprehensive EU database on medical devices and of a device traceability system based on unique device identification (UDI)

- The introduction of an implant card containing information about implanted medical devices for a patient

- The enforcement of the rules on clinical evidence, including an EU-wide coordinated procedure for authorisation of multi-centre clinical investigation

- The strengthening of post-market surveillance requirements for manufacturers

- Improved coordination mechanisms between EU countries in the fields of vigilance and market surveillance

[1] Campbell B. Regulation and safe adoption of new medical devices and procedures. Brit Med Bull 2013;107:5–18.

[2] European Commission. Guidelines on medical devices: guidelines on clinical investigations; guide for manufacturers and notified bodies. MEDDEV 2.7/4. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/ documents/10336/attachments/1/translations (accessed 26 June 2019).

[3] Council Directive 93/42/EEC 14 June 1993 concerning medical devices. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/ legal-content/ENTXT/?uri=CELEX%3A01993 L0042-20071011 (accessed 26 June 2019).

[4] French-Mowat E, Burnett J. How are medical devices regulated in the European Union. J R Soc Med 2012;105:S22–28.

[5] Boulton AJM. Registration and regulation of medical devices used in diabetes in Europe: need for radical reform. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2013;1:270–2.

[6] National competent authorities list by EMA. Available at: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/ eu-partners/eu-member-states/national-competentauthorities-human (accessed 26 June 2019).

[7] European CE technical file or design dossier compilation for medical devices by EMERGO. Available at: https://www.emergobyul.com/services/europe/ technical-file-preparation (accessed 26 June 2019).

[8] Kramer DB, Xu S, Kesselheim AS. How does medical device approval regulation perform in the United States and the European Union? A systematic review. PLos Med 2012;9:e1001276.

[9] European CE marking strategy for medical devices by EMERGO. Available at: https://www.emergobyul.com/ services/europe/ce-certification (accessed 26 June 2019).

[10] Jefferys DB. The regulation of medical devices and the role of the Medical Devices Agency. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2001;52:229–35.

[11] Sorenson C, Drummond M. Improving medical device regulation: the United States and Europe in perspective. Milbank Qrtly 2014;92:114–30.

[12] Bright J. European medical device regulatory law and product liability. J Hosp Infect 1999;43:169–73

[13] Greco C. The poly implant prosthèse breast prosthesis scandal: embodied risk and social suffering. Soc Sci Med 2014;147:150–7

[14] European Commission. Regulatory framework for medical devices. Available at: https://ec.europa. eu/growth/sectors/medical-devices/regulatoryframework_en (accessed 26 June 2019).