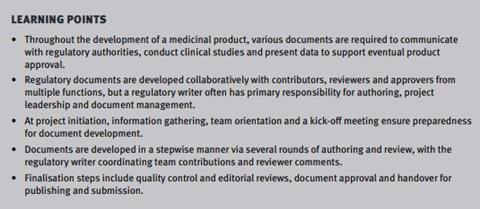

Regulatory writers lead the development of high-quality regulatory documents by working in collaboration with colleagues across multiple functions. Document development is a multistep process with the regulatory writer acting as project leader. This article describes each of the stages of the process and suggests best practices for achieving timely project completion and document delivery

Introduction

Throughout the development of a medicinal product, various documents are required to conduct clinical studies, communicate with regulatory authorities and demonstrate the product’s quality, safety and efficacy to obtain eventual marketing approval. These documents may focus specifically on clinical, nonclinical or chemistry, manufacturing and controls (CMC) data or they may be cross-disciplinary. Various legislation and regulatory guidance exists at national and regional levels to provide recommendations on the content and format of specific document types. In addition, the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH), which was established to harmonise regulatory documents and submissions across countries and regions, publishes guidance that applies internationally.[1] Most notable is the common technical document (CTD) format for regulatory dossiers. A tabulated summary of the various types of pre-approval regulatory documents, together with the associated guidance for each document type, is available elsewhere.[2]

Regardless of document type, the objective of any regulatory document is to present data and the key messages and conclusions of those data to support a particular regulatory outcome (eg, to gain approval for a clinical study programme or a change in manufacturing process). Inevitably, the data and content on which a regulatory document relies come from a variety of sources, with contributions from functions across the drug development spectrum (eg, pharmacokinetics, clinical, biostatistics, CMC, nonclinical and regulatory affairs). Although the development of regulatory documents is ostensibly a collaborative endeavour, the primary responsibility for both document authoring and stewardship falls on a professional regulatory writer, who is specialised in scientific communication and has expertise in the regulatory requirements of different document types. Regulatory writers act as primary author, project leader and document manager and thus play a pivotal role in ensuring documents are prepared to the highest standard and are finalised in a timely manner in line with the goals of the product development programme.

Despite many organisations having standard operating procedures (SOPs) and established processes in place for the development of regulatory documents, these tend to be vague and often lack detail on best practices and the particular nuances of the process. This article provides a detailed description of each of the stages of the document development process, from initiation to finalisation, as well as recommended best practices.

Overview of the document development process

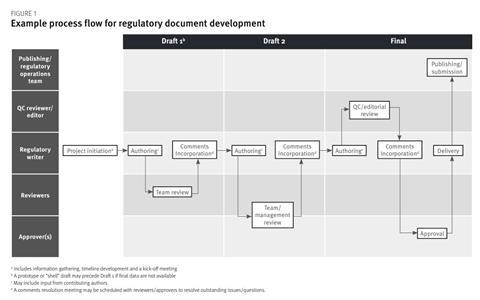

Regulatory document development follows a logical sequence from start to finish. The complexity of the project workflow depends on the type of document, the volume of data on which it is built and its interdependencies with other documents (ie, the process for a CTD module forming part of a large submission will inevitably be more complex than that for a standalone document such as a fast-track application). Also, processes may vary between different sponsors and vendors. However, in general, there are several key steps involved in any regulatory writing project, and these are described in the subsequent sections. An example process flow is provided in Figure 1.

In addition to being the primary author for the document, a regulatory writer is often responsible for the document throughout its development and acts as the main point of contact for the project. As there are often multiple personnel involved in document development – including contributing authors, reviewers and approvers – as well as numerous auxiliary functions that will need to be kept apprised of progress throughout, a regulatory writer needs to be an effective project leader to coordinate input from numerous sources and ensure that the document is delivered on time. Proactive communication is essential to keep the team engaged and minimise delays, and the regulatory writer should take ownership of scheduling meetings, sending calendar invites and reminders for key timeline events, following up on meeting actions and chasing outstanding input.

Project initiation

At the initiation of a new project, key information needs to be gathered before authoring can begin. An organisation’s SOPs are often the first port of call and give an overview of the process to be followed, as well as key roles and responsibilities, but it is often prudent to schedule a preliminary meeting with a project manager, regulatory lead or other personnel who can provide more detail. Recommended questions to ask at this stage are:

- What is the product, its stage of development and its regulatory history (ie, what other documents exist in draft or approved state), and what is the goal of the particular document in question?

- What source data will the document rely on, who is responsible for delivering these and when will they be delivered?

- What is the deadline for the project (ie, target approval date), and is this driven by an external deadline (eg, a target submission date for a particular regulatory authority)?

- Are there any other important dates to be aware of (eg, a meeting date for scientific advice, study interim analysis or deadlines for other modules of the same submission)?

- Will the document require significant contributions from key functions (eg, clinical pharmacology, CMC, medical or biostatistics), and which individuals from these functions will act as contributing authors?

- Who are the document’s reviewers and approvers (including their contact details)?

With this information to hand, the regulatory writer can begin preparing a timeline. A well-structured timeline helps to ensure timely document delivery by guiding the team through the project, setting out visually the process flow and delineating each part of the process. Since regulatory documents are part of a broader development programme and are likely to have many interdependencies with other documents, it is important to work in concert with the project leadership team (eg, regulatory or medical lead and programme manager) to ensure the proposed timeline is aligned with those of other related components. Timeline duration and structure for a specific document type may be governed by an organisation’s SOPs. Also, the project budget and any service agreement between sponsor and vendor, if applicable, will need to be taken into consideration. However, for projects with aggressive deadlines, some creativity and flexibility is required, and it may be necessary to combine or shorten specific steps in the process. A variety of project management software exists that can be employed for timeline preparation, but a spreadsheet programme is also sufficient.

Once the timeline is prepared, at least in draft form, a kick-off meeting (KOM) should be scheduled with the proposed contributing authors, reviewers and approvers. It is beneficial to prepare a meeting agenda in advance, and a slide deck or other presentation format provides a useful visual aid during the meeting. Copies of these can be provided to the team for reference. The goals of the KOM are to:

- Provide the team with an overview of the project background and aims of the document

- Introduce the team and confirm roles and responsibilities of the regulatory writer, contributing authors, reviewers and approvers

- Gain agreement on the project timeline. (It is useful to note team members’ planned out-of-office time if there are likely conflicts with key timeline events, and in such cases, it should be confirmed whether tasks can be delegated.)

- Discuss the strategy for document development, applicable regulatory guidance, key data driving the content (including who will provide this and when) and gaps in knowledge

- Establish best practices for authoring, review and approval, referring to relevant SOPs where applicable

- Answer any other questions to ensure preparedness for the project.

A project timeline will likely include a comments resolution meeting (CRM) after each review period. It is wise to schedule placeholders for CRMs as early as possible, since reviewers are likely to be involved in multiple projects simultaneously and their calendars can become very busy. Invitees for a CRM should be limited to those team members who directly participated in the preceding review.

Authoring

Following the KOM, authoring can begin in earnest. Many organisations use an electronic document management system (EDMS) as a repository for regulatory documents and for managing the review and approval process. Ideally, the regulatory writer should restrict access to the document and ensure only one copy (the “master document”) is in use. Use of an EDMS is beneficial in this regard as such systems possess access controls in the form of document check-in/check-out. During authoring, it is sensible to check out the document to ensure that no other changes are made by other users. If it is desirable to author outside of an EDMS, the document should be imported into the system at regular intervals to prevent loss of content and to log the document’s version history and audit trail (per the principles of good document practices[3] and ICH recommendations on computerised systems[4] and document storage for clinical studies[5]).

During authoring periods, the regulatory writer is the main contributor to a document’s content and often works autonomously to draft the document using applicable regulatory guidance, knowledge of the regulatory development programme, available background information and source materials. Sources might include tables, figures and listings; literature references; scientific reports; other regulatory documents and professional judgements. Document templates are invaluable in aiding standardisation and compliance with regulatory requirements.[6]

It is important to bear in mind the document’s objectives and target audience (ie, a regulatory authority) and to focus on the quality of the document in terms of its accuracy, clarity and consistency. As part of the finalisation process, documents will go through quality control (QC) and editorial reviews, and the success of these quality checks will depend on the completeness of the document. Thus, a “quality in, quality out” philosophy should be at the forefront of the regulatory writer’s mind throughout document development. It is good practice to ensure that every draft of a document is “delivery-ready” and of the highest quality before sending for review to ensure that a review period is as productive as possible. Conducting QC/ editorial reviews incrementally (ie, before each draft is sent for review) is beneficial in this respect. Use of automatic proofreading software is also advantageous.

Placeholders can be added for pending data and items requiring input from other team members. For some documents, it may be necessary to include one or more contributing authors, particularly in cases where the content relies on novel information or strategic input from multiple functions (eg, briefing documents and responses to agency questions). In such cases, input is best gained by assigning an authoring workflow (via the EDMS) or enabling collaborative authoring, if this feature is available. Failing this, the regulatory writer should gather contributed text via other means (eg, a cloud-based file sharing system) and merge it into the master document. Copies should be filed to a suitable location for QC review.

Document review, comments incorporation and resolution

When authoring is complete, the document will be assigned for review to gain feedback on the content, answer specific questions and further develop the document. Depending on the stage of the project and the processes (ie, SOPs) being followed, reviews may be conducted by functional subject matter experts (team review) or leadership (management review), or both. In cases where management reviewers are not the approvers (ie, the signatories) of a document, a separate “approval review” may be necessary to allow the approvers the chance to peruse the document before the approval stage. A review workflow may be assigned directly within an EDMS or via real-time collaboration software. Both options allow reviewers to suggest changes to the content and make comments. A useful feature of these systems is automatic reminders, which are sent as the review deadline approaches. During each review period, there may be individuals who need to be aware of the document but do not need to amend or comment on the content. In such cases, a “view only” task can be assigned.

When the review deadline is reached, the workflow should be closed to prevent any late comments or changes. Depending on the system used, a report may be available listing all reviewer comments and changes; otherwise, an annotated copy of the document should be used as the review report. The report should be filed to an appropriate location as a source for QC review. Although it should be discouraged, some reviewers may need to complete their review by using an offline copy of the document (eg, if they have software issues). Such documents should be merged with the review report as soon as possible after completion of the review.

Following completion of a review period, the regulatory writer should begin incorporating changes and addressing comments. It is sensible to keep the annotated document separate from the master document and to respond to each comment to note the action taken (ie, “change incorporated” or “change not incorporated” with a reason). Any items that cannot be resolved at this stage should be flagged for discussion at the CRM, with the list of outstanding items forming the CRM agenda. If there are many items requiring discussion, it may be better to contact specific reviewers individually to try to resolve those items. During the CRM, the agreed resolutions to each item should be noted in the report in real time. Any items requiring follow-up should also be documented. These notes form the minutes of the CRM and should be circulated with the meeting attendees. Once all items are resolved, the regulatory writer can incorporate the agreed changes into the master document.

Document finalisation

Although, as mentioned, it may be desirable to perform a QC review incrementally, the final QC review is the last opportunity to catch any errors or inconsistencies before document approval. QC and editorial reviews are conducted by a technical editor or other expert in document quality and are essential for verifying the content of the document and ensuring its style and formatting meet the required standards. QC and editorial reviews may occur simultaneously or separately. Many organisations have established QC processes in place; further detail is provided by Li et al. [7]

With the document complete and all outstanding reviewer comments, questions and QC findings fully resolved, internal approval by the document’s signatory/ signatories should proceed without any issues. Document approval is commonly achieved via an EDMS approval workflow. Once approved, the document can be transferred to an organisation’s publishing/regulatory operations groups to prepare for external submission. At this stage, it is courteous to notify the team and other relevant personnel of document approval and to thank all individuals who were involved in the project.

To register your CPD, please use our CPD tool: https://www.topra.org/TOPRA_Member/Professional_Development/CPD_and_lifelong_learning/CPD_tool/TOPRA/TOPRA_Member/CPD/MyCPD.aspx

References:

[1] ICH Guidelines. Available at: ICH Official web site : ICH (accessed 8 March 2021).

[2] Billiones R. A guide to pre-approval regulatory documents. Medical Writing. 2014;23(2):84–5.

[3] European Commission. EudraLex: The rules governing medicinal products in the European Union. Volume 4: Good manufacturing practice. Chapter 4: Documentation. Available at: EudraLex - Volume 4 (europa.eu) (accessed 8 March 2021).

[4] European Commission. EudraLex: The rules governing medicinal products in the European Union. Volume 4: Good manufacturing practice. Chapter 4: Documentation. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-4/ chapter4_01-2011_en.pdf (accessed 8 March 2021).

[5] ICH. Guideline E6(R2): Guideline for good clinical practice. Chapter 8: Essential documents for the conduct of a clinical trial. Available at: https://database.ich.org/sites/default/files/ E6_R2_Addendum.pdf (accessed 8 March 2021).

[6] Billiones R. Document templates for medical writers. Medical Writing. 2014;23(1):17–21.

[7] Li H, Hanna K, Petteway S. Ensuring quality of regulatory clinical documents. The Quality Assurance Journal. 2010;13(1–2):14–20.